Lost and Found

There isn’t much left of back then besides this old picture that I keep in my cell buried in my Bible. It is in great condition for how old it is. Not bent at all, nor faded all that much. I didn’t tape it to the wall because we weren’t allowed to have pictures on our wall. They weren’t our walls, they reminded us, they are the state’s walls. But even if we were allowed, I wouldn’t have hung it up. I’d be afraid someone would steal it out of spite and tear it up, and if they did I would probably catch a murder charge. Sometimes I am still in prison, even though I am out.

I’ve been a million places since back then, when I was three-years-old on my brother’s lap, 1980. I had long, golden-brown hair, a chubby face, and a big smile. I wore a light blue Superman shirt and I remember telling my brothers that I wanted to grow up and be Superman when we were all talking about what we wanted to be on our way to Bob Bay’s grocery store. When one of my brothers laughed and I sensed in his sniggering that I couldn’t be Superman, I said if not Superman I wanted to be a car. No particular make or model. Just a car. Red, though. Then all three of my brothers laughed and one of them punched me in the arm saying I couldn’t be a car. He would have called me a dumbass, a fag, a dweeb, or a fart knocker if my mom wasn’t there. It wasn’t true that you could grow up and be whatever you wanted to be. That was a hard lesson for me to learn.

Sometimes when I am sad I look at that picture. My dad wasn’t in it because he never liked to have his picture taken. Or he knew he wasn’t going to stay forever and didn’t want photo evidence of ever being there in our family. My mom had big black hair, a poodle of a perm, and my brothers were happy-looking goofballs in their banana-yellow baseball team t-shirts, smiling with the pride of the Yankees. You could see how much my mom loved us. We looked like her ducklings. They were the bright yellow ones and I was the black one. I’d say I was ugly but there was never anything ugly about me and I used that to my advantage all throughout my life until life started asking for its inevitable payback. A life I have wasted away strung out and in jails and prisons all over the country.

Forty-two years have gone in the blink of an eye, but I can still taste a Fat Cat’s pizza and feel the comfort of our brown and beige living room carpet under my bare back. I can still feel my brother’s innocent tickles at night on my back when we would draw baseball team logos and guess what we drew, feel the sheet over me and the floor fan we put in the window as an air conditioner, and still see The Dukes of Hazzard on the cabinet TV and hear the little static boom when it was turned on and feel the knob in my fingers. I can hear the click of the TV dial that went up to thirteen and no further, until there was the HBO box. When late at night our once wholesome TV became a whorehouse. It all went to shit when they installed the cable box and it went to 34, if you ask me.

The sounds of every Atari game are trapped in my head and on occasions they spill out in the open like my mind is a crowded arcade for a dozen fat kids with giant pockets bursting full of quarters. Pac-man eating power pellets. Q*bert hopping up that pyramid. The squeal of Pole Position tires on television asphalt or growling on the berm. Pitfall Harry swinging across a pond of crocodiles on an eight-bit vine searching for a woman. At one time or another I wanted to be Pitfall Harry until I discovered Indiana Jones on HBO. When I was nine or ten I thought I could be him someday. I could discover something no one ever found or reclaim something someone lost. Something so great that I would be in the newspapers and remembered. Known and never forgotten like dead uncles and grandparents, people who died after a life in the factory. It mattered to me then to be known, and I never thought I would ever purposefully try to live anonymously. But at some point I got lost and I couldn’t find myself. The eighties, Ronald Reagan, E.T., Rambo, the warm watery eyes of my elementary school principal were lost and all I wanted was to go back to where I belonged. Where I was safe.

Maybe I look at the picture because I like to remind myself that I was once good and pure, and so looking at it reminds me that I wasn’t always this way, a number and a convict. A felon who can’t vote or even own a gun. Who can’t work good jobs or get certain loans. When I was a kid I loved animals and other people too much. I loved Sunday school and my brothers with all my heart. I loved the Junkyard Dog and WWF wrestling. Wrestlemania and Hulk Hogan body slamming Andre the Giant in the Pontiac Silverdome. I loved my mom so much so that I cried when I thought about her dying, and I could never spend the night in another house. I cried when I saw dead animals along the road and I never once turned away a stray dog or cat that came to our door.

I was afraid of the dark and aliens that didn’t look like E.T. I was afraid of the unknown that is now known to me. Maybe I knew I would turn out this way. Maybe it was because I stopped believing in Santa Claus and I was spoiled, or because my dad finally left us though he was never really there to begin with. Maybe it was because the factory shut down. Or Happy Harry. Or because of grunge music or the girl who broke my heart. Or because I was bumped down to seventh in my little league batting order, rather than first. Maybe it finally found me. It. The inevitable it that finds everyone. The it that steals from everyone. Not like the book. Not like Pennywise, or the spider. But the it that collects from all of us what is only ours to keep for so long. The thief of our innocence. Our childhood. What we can never get back when its gone.

I am not inside state walls anymore. I live anonymously in California. I got a job when I want it doing construction and live with a widowed woman who is pretty and wealthy. Her luxurious cabin sits in the woods in a sprawling grove of towering redwoods and there is a pond that I take her grandkids out onto and teach them how to fish. They like to paddle out in a canoe her deceased husband never finished that I finished for him. I became Pappy at some point over the past year. I couldn’t ever imagine being a grandfather and I certainly never had any example of how to be one, other than what I saw on The Walton’s growing up. I could live out my life here, comfortably, and no one will ever bother me. No one will ever know that I was on felony paper back in Michigan for a bank robbery I did eight years on, and that I am wanted in two other states for similar crimes.

I hung that picture up on my bedroom mirror and at night I sometimes look at it and smile at the little boy smiling back. Maybe when I die I will get a chance to meet him again. To be him again. I tried to stay in touch with my brothers as best I could, but being on the lam means you cannot stay in touch with anyone too much. It also meant I never drove anywhere in case I was pulled over. Or used my old name at all. Somewhere along the road I buried my old self and was reborn to a new identity, Charlie Fisher. The boy I once was in that picture is long since gone. Like the Berlin Wall or Max Headroom. Lost somewhere to it in Pee Wee’s playhouse.

I watch these new grandkids of mine as Karen and I sit on the giant porch and drink sun tea. They don’t play like we did when we were kids, they play new games I don’t know. They catch Pokemon, not fly balls. They don’t play wiffle ball, or Frisbee, or Smear the Queer, or Fag Tag. But one game they still play is Hide and Seek, which is really just another way of saying Lost and Found. And watching them I see my brothers and I running around the neighborhood over drive ways and chainlink fences to hide in overgrown yews in front of basement windows. I can feel cobwebs on my elbow and hear the sounds of plastic big wheel tires burning across street cinders. They don’t play Cowboys and Indians. Hell, they’re not even allowed to say Indians, anymore.

Occasionally, I creep on my brother’s Facebook page to see how everyone is. I watched my mom die this way years ago when I was in Oklahoma strung out on dope and living on an Indian reservation along the highway that sold “real” Indian jewelry and tomahawks to tourists. But that was a long time ago. The little boy who cried thinking of her dying was sunburnt and high running from a six count felony trafficking charge as his mom took her last breaths. Maybe I had accidentally become my dad. But hell, I can’t even remember what he looks like.

I am happy here, with Karen and her grandkids. Time stands still out in that canoe in that beautiful pond dug into those enormous redwoods where I would sometimes sit at night and look up at the stars and the moon. I wasn’t afraid of the dark or aliens anymore. I wasn’t afraid of being lost. Being lost was my way of life. I was only afraid of being found.

Only one brother of mine has Facebook. Daniel is 48, six years older than me. He posted today that his youngest daughter needed a kidney or she was going to die. He was never dramatic and was always a quiet and personal person, so I knew the post was as serious as it sounded. She is fourteen and ten down on the donor list. The post made it sound as though they had given up and were accepting the cruel reality that despite everyone who has two kidneys, and everyone who dies on a daily basis, a kidney wasn’t going to come. Daniel encouraged everyone to pray and everyone commented that they were going to pray. He also provided a link for people to donate to a research center that researches the type of disorder she has. I closed my laptop and looked up at the picture on my bedroom mirror.

I had never met my niece, Sophie Porter. She was beautiful and thin and had big blue eyes like her dad. Fortunately, she got the rest of her looks and features from her mother, I joke. She was in drama club and in her freshman year of high school with a 4.4 GPA. She was a soccer player and once broke her arm in seventh grade during a tournament. I knew all of that from Facebook, from an anonymous account. I never dared to like anything I saw for fear of being found and put back in prison. Being lost had a sole advantage. Freedom.

But I packed my bags and Karen stood behind me in the open door. I heard her come in with the sound of robots touching the walls in Tron mixed with the sound of Centipede being shot to a thousand pieces. She said she knew that this time would come, but she hoped it would be later than sooner. We met in a suburban winery where I was supposed to sell some X to someone who never showed. I lied and told Karen my date stood me up when she asked why I was there all alone. A friend drug her out to get over her husband’s death from the year before. She told me I was a wanderer. She saw it in my eyes. I suppose that I am.

“Where are you going?”

“Home,” I said softly. My voice cracked. I suppose I really loved her because I felt acid bubbling in my stomach as I said it. I thought of unpacking, but instead I closed my suitcase and zipped it shut.

“Will you come back?”

I shook my head no.

“Why?”

“I have to.”

“They’ll arrest you.”

I looked back at her, surprised she knew my secret.

“You think I didn’t know?” she grinned painfully. “I did my homework, David Porter. Not Charlie Fisher.”

“I got to go, Karen.”

She shook her head and stepped away from the bedroom door. I grabbed my suitcase and walked towards her. I stopped as though I wanted to say something, but I just stood there for a few seconds and then without saying anything, walked away.

“You can take the Rubicon,” she offered. I said thanks.

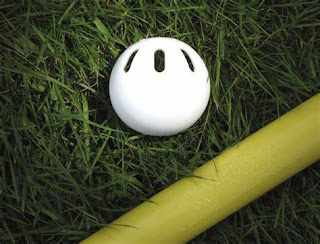

I drove the speed limit all the way home to Michigan. I slept for five hours somewhere in Oklahoma near where I was once strung out for a year of my lost life. I thought a lot about Daniel when I drove home, Sophie’s dad. He was the brother I was closest to, being that he was closest to me in age. He taught me how to play baseball. How to throw a curve. He turned me on to The Doors. And for hours and hours we played football and wiffle ball in the backyard, depending on the season. We kept wiffle ball stats in binders on notebook paper. Crushed balls over the house and out into the front street. Duct-taped balls that when fouled off banged loudly off the neighbors back kitchen window glass. We’d drop our bat and run inside. If they were feeling charitable, the ball would be in our backyard when we came back out. If not, we would wait until tomorrow when all was forgotten. Wasn’t us, if they ever asked.

Wiffle balls don’t break glass. Not even taped once or twice. But they sound like it. I hit 33 homers in the summer of 88 and I beat him in the World Series that year, but he threw it. Like the 1919 Sox. He threw it because of it. I was losing it. And he knew we only had one summer left, at most, before we would never play again. He graduated high school the next year and lost it years before, but for some reason, he held on a little longer than most. Probably for me.

They were all in the hospital room when I arrived. No one spoke when I walked in, but their faces said everything for them. Machines beeped and whizzed and the room smelled sterile and clean. Their mouths dropped and their eyes widened and didn’t blink. I was a ghost. Like the ghost runner on third base.

“David?” Ed said at last. Ed was the oldest. Ed Jr. Little Ed. Big Ed was my absent dad. All my brothers hugged me and introduced me to their wives and kids.

“What the hell are you doing here?” Daniel asked, scared that SWAT would swoop in and arrest me at any moment. He shut the door behind me.

“Heard Sophie needs a kidney.” I said her name like I knew her. Like I had been at her birth and birthdays for fourteen years. She lay in the bed looking up and smiling at me. She must have heard stories. She waved a shy wave and her eyes twinkled. My God, she was a beautiful angel. “I got a spare,” I smiled looking at her.

Daniel spoke up. “You gotta get out of here. Once they know you’re you they’ll arrest you! You’d have to fill out forms and...” He stopped short as he looked at me. He knew I wasn’t going to leave. It was the same look we exchanged about thirty two years ago in our backyard when it was a 3-2 count with bases loaded and he told me he was going to throw a curve, Game 6 of the World Series. I grinned at him knowing he didn’t trust his curve for a strike and would never throw it. I crushed his fastball over the house for a walk-off slammer. I flipped my bat in celebration and he hung his head. I went on to win Game 7 in a rout and he retired. I hung out in the backyard for the next few summers by myself tossing the ball up in the air and hitting it with the yellow bat. I can still feel the bristly grip of that bat in my palms.

“Thank you,” he said with tears in his eyes.

I shook my head as though it was no big deal. “I’m a match. I checked with the registry. And I’m clean, in case you wondered. All those years of drugs. Who would have thought?” I laughed a little to ease my nerves, but everyone just looked at me uneasily. The ugly duckling had returned.

“They’ll put you in prison,” Daniel said finally.

“I know. But how many times did you bail me out? How many times did I burn you and Lisa when I ran?” Lisa was his wife. She was in the background and cringed.

Sure enough the nurses had me immediately fill out a thousand forms and I was not Charlie Fisher anymore. I was once again David Porter. The doctors ran some blood tests and they gave me my own room next to Sophie’s. They checked my vitals and half of us were in my room and half of us were with Sophie. Before the surgery I was able to sit in the room with her and my family, and I hadn’t felt that good in thirty years. There is no drug better than the love of a family. I really wished I had children. Or if I had children, that I had hung around long enough to meet them. I suppose there could be kids of mine out there. In Abilene or Duluth. It made me sad to think about it, so I smiled and I tried to think about something else.

It wasn’t more than an hour before a police officer came into the room and asked to speak with me alone. He told me I would be placed under arrest after the surgery and I told him thank you for waiting until after the surgery to do so. He shook his head solemnly. I would be allowed to recuperate in the hospital and hospital police would shackle me to the bed while I did. I said that I understood and he walked out of the room.

The surgery took place the next morning. The kidney fit like a glove, Daniel told me when I woke up. Her body accepted it and she was doing just fine. She would be okay, he cried. I said that was good and I reached over and pulled that picture of us as kids out of my hospital Bible that lied on the table next to the bed. I handed it to him and he smiled. I was groggy from the anesthesia. I told him thanks for rescuing me from Harry’s. His face went white and I knew he probably hadn’t talked about it in thirty years.

Happy Harry was a child molester who lived a block over from us growing up. He abducted me when I was six, when I got away from my brother while we were playing Hide and Seek at the park. He was called Happy Harry because he always smiled. His house was green inside and dimly lit. It smelled like plastic and his breath smelled like stale beer and cigarettes. Daniel found me, busted down the back door, pushed Harry away, and grabbed me so hard he broke my arm. I don’t know how he knew where I was, but he knew. We ran home and we never told anyone what happened. We said I fell to explain the arm. Eventually, they arrested Harry, years later. I told Daniel thank you again, weakly, and drifted back to sleep.

When I woke up all three of my brothers were standing there over me like I was dead. Ed used to stand over me like this when he would hit me with something in the head. I would lie motionless afterwards so not to get hit again. Like a possum. He would laugh for a minute and then say, “I know you’re faking, geek.” When he said that, I knew I had him. When he was genuinely concerned that he may have killed me this time. So for old time’s sake, I lied there and pretended I was dead, though I could see them through my squinty possum eyes. Finally, I caught him smiling when he realized what I was doing. He frogged my leg, for old time’s sake.

I was shackled to the bed and realized this was it. The end of everything. But it was a good ending. I was sore as hell, but the feeling in my heart more than satisfied the pain, and my internal organs made no complaint for the one thing I spent my life with that was broken felt suddenly healed. I wouldn’t go back to prison. I’d hang first. A self-imposed sentence for a wayward life of crime. My brothers stayed and talked for a while and kept me updated on Sophie’s condition. Then after a few hours more, Sophie wheeled in on a wheelchair and told me thank you. Everyone else left the room and she stuck around and talked for a while and I started feeling sad that I never had a daughter. Then I pulled out that picture and showed her how goofy her dad looked when he was little. She laughed. She said I was cute in my Superman shirt. Then she looked at me and smiled, saying, “That is what you are, you know?”

“What?”

“Superman. You are Superman.”

I laughed thinking of what I said when I was a kid. How I wanted to be him. “Sophie, I’m not.”

“You are to me,” she said weakly.

I smiled and nodded my head. I held her hand in gratitude. I almost forgot I was shackled until the chain jiggled on the bed rail. She looked down and frowned, then wheeled closer to the bed. “I owe you, Uncle Davey.”

“You don’t,” I replied. “You already repaid me.”

“How?”

“By saying what you said.” She smiled and looked down at the picture again before handing it back to me.

“I can’t believe grandma had a fro.”

I laughed and nodded my head. “Have you ever played wiffle ball with your dad?”

“Wiffle ball? Like baseball, but plastic, right?”

“Yeah.”

“No. He talks about it, though.”

“Well, do me a favor. When you get out, go buy a bat and ball and challenge him to a game. Just watch out for his knuckler. The bottom will drop out right before you swing. But you can always tell when he is going to throw it because he will bite his bottom lip and look at the ball to check his grip. Some things never change.”

She smiled. “I will,” she promised. “I’d like that. Maybe you can...”

“No. Not where I’m going, Sophie. But I’ll be fine.”

After a while longer she reluctantly said goodbye and wheeled herself away. I spent the next 24 hours catching up with family and I felt as good as I had in decades. It was a Sunday night when the officer came into the room and told me they would be there to get me Monday morning to take me to jail. He spoke with compassion and a touch of sympathy in his voice. I was reading the Bible when he walked in and it was on my chest. He wasn’t wearing a uniform. He was in jeans and a cowboy hat like he was going to a rodeo or something. He didn’t look like much of an officer at all. He sat down by the bed and spoke to me. He took the big tan hat off and held it in his large hands and looked up at me from the chair.

“I don’t know why men do the things they do, Mr. Porter. They just do ’em, I guess. Don’t know why you led the life you led and I led the life I led. But I ’specially don’t know why you’d come back here after all these years to save the life of a niece you never met before. Guess maybe you ain’t that person who robbed them banks and cash-marts and trafficked all them drugs for so long anymore. At least, not in your core. Maybe we don’t really know people much at all, I figure.”

“Maybe so,” I agreed. I lied back and a flash of pain struck me around my absent kidney. I did my best not to press the pain button because I didn’t want to be a junkie anymore after seven years sober. That was too many years to go back now. “What’d you wanna be when you were a kid?” I asked the officer who was still sitting there pawing at his hat.

He held it up and smiled. “Can you guess?”

“A cowboy?”

He nodded yes. “Like Clint Eastwood. Only I wasn’t killin’ nobody that didn’t need kilt. What about you?”

I smiled and told him Superman. He laughed and put his hat back on. “Able to leap tall building in a single bound. Them banks been robbed ain’t gettin’ any money back with you in prison, them cash-marts, neither. And them drugs you sold, guess people did buy them willingly and it was a long time ago now. Be a shame if you weren’t here when they came to get you in the mornin.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out a key and left it on the table beside my bed. Then he nodded, put on his hat, and left the room and I never saw him again. I suppose I could say he rode off into the sunset.

I was lucky they had left my clothes in the room and I ditched the gown and bolted in the chaos of shift change. I’ve ran from hospitals before and there is an art to it. All you have to do is avoid eye contact and hospital police who are nothing but glorified security guards. After you’re through the last set of doors, you got nothing to worry about. I left a letter for my family. And I left the picture for Sophie. I knew she would keep it as I kept it. The Rubicon was where I parked it and being in Karen’s name I had nothing to worry about in driving back to California except getting pulled over, so I drove the speed limit and I thought of my mom and cried. When she gave me a bath when I was a baby she used to always play with my toes in the tub and recite the little pigs rhyme. I would giggle to tears. I can hear my bath water splash and her sweet voice still deep in my cracked mind.

I got home 36 hours later. Home, I said. Even to myself I said it and it echoed in my mind like Asteroids falling in the cabinet TV. Karen was happy to see her Jeep pull up and even happier, she said, to see me in it. She was afraid I’d return it but not myself, which made me think of taking Coke bottles back to Convenience, a quick-mart near my house where I grew up. She never asked where I went and I never told her. It didn’t seem to matter that she knew. But she acted as though she knew I had done something good for someone because she said I seemed much happier.

I kept up with Sophie through Facebook, anonymously, of course. She changed her Facebook profile to the picture I gave her of me and my brothers and my mom. I printed off a copy and framed it. She said she smashed her dad’s knuckler for a triple, but he beat her 9-7 in extra innings the day before. She said she had a hard time understanding ghost runners, particularly when a ghost runner on third runs and when he doesn’t. I laughed and told her it would come. To keep playing. She said she never saw her dad so happy and he told her all about when we used to play. She said she loved me and I replied in kind. Then I closed the laptop screen and Karen and I went to bed. It came back to me. In the dreams that come somewhere between wake and sleep. It. I heard my mom’s voice and I was very happy just like I was when I was a little boy. It sometimes comes back. You just have to let it.

This little piggy went to market. This little piggy stayed home. This little piggy had roast beef. This little piggy had none. This little piggy went wee, wee, wee all the way home.

Comments

Post a Comment