A Means to an End

"Your money's on the dresser. But your salvation is free."

"Salvation don't pay the bills, reverend."

He lit a cigarette and took a long drag, regarding her against the knotty-pine wall of the motor lodge room. He didn't smoke normally, but Bob, his alter-ego did, and Bob was in charge now. A cloud of smoke rose between them. As she got dressed, he grabbed the Gideon's from the nightstand. Rifled through, always loving the sound of those thin pages which reminded him of rice paper. Crisp and clean. He covered up, wishing to stay in bed all day. He looked a little like a whale if it had arms and legs and a gray mustache. If it were balding and pale and had a hairy back. He wasn't handsome in the least, but he was charismatic. That is what matters when you are a reverend.

"Call me?" she asked putting the cash in her purse. The shower hissed in the background. He always turned on the shower so to muffle the sound of their "lovemaking" in case someone in the next room was listening.

"No. This is the last time we'll ever see each other. I am giving all this up, Daisy. I am going to be faithful to my wife and be the preacher I always wanted to be," he proclaimed somberly.

She laughed. He laughed, too.

"Spend that money well. A lot of good people worked awful hard for it."

"I work awful hard for it, too," she grinned. "Wouldn't you say so, Bob?"

He smiled and exhaled another gray cloud. "I would say so, Daisy."

She smiled putting on her shoes.

"You see there," he said. "Jesus is at the window. Peeping in. He knows all and sees all. I can't be livin' this way, bein' a man of God and all."

She turned to look in her naivety, as though Jesus would actually be there as he was on a velvet painting in her grandma's living room every time she visited. Forever tormented, collapsed under the weight and strain of his cross. She couldn't remember if he were crying or not. If a tear rolled down his bloodstained cheek. All she recalled was that the painting was dark, red and terribly sad to look at when you're a six year-old kid.

The reverend laughed at her for looking at the window.

"Well, ain't he s'posed to forgive...and all that."

"Sure, darling. Which is why I'll be back next Tuesday," he smiled. "So he can forgive me. Again."

"Well, I'll pencil ya in. Ya know, you look like Gene Hackman in a certain light," she told him again as she had said a few times before. "If there was a movie about us, that's who would play ya, Bob. Gene Hackman. Who ya think would play me?"

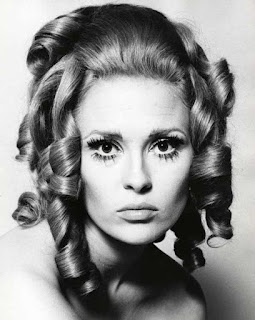

"That's easy," he snickered licking his thin lips with his already sore tongue. "Faye Dunaway."

"Faye Dunaway," she repeated longingly. She remembered her from Chinatown. From Bonnie and Clyde. And something else. She caught a glance of herself in the mirror above the dresser and she saw the resemblance. She was happy for a second, but those seconds never lasted. It was artificial. They come and go like rain comes and goes. Like sunshine comes and goes. Like men come and go.

But the reverend was right. She looked remarkably like Faye Dunaway, so much so that she could get a bus ticket to Hollywood and get a job as a double. She could do commercials. If ever they had some kind of Faye Dunaway lookalike contest, surely, she would win. She knew the resemblance was true and everytime she had her hair done, she would say only two words to Bette, her beautician, "Faye, please."

"Faye it is," Bette would reply. Bette with an e. So she curled her in hair like Faye's was in that one picture.

In an alternative universe, perhaps she actually was Faye Dunaway. Perhaps, this was a movie role for a movie she hadn't seen. Perhaps she didn't exist at all, but Faye did and Faye was she but she was not Faye. And somewhere out there was Scarlett O'Hara, and Dorothy Gale and every character in the universe existing yet not existing at the same time. Faye was simply playing her and at any moment the movie would end and she would end with it. Credits for a eulogy.

It was hard to wrap her mind around, but the thought reoccurred to her over the next week or so. It did again as she sat in a diner and ate a cheeseburger. As a handsome man in a Navy uniform made a modest but definite pass at her. He was an extra with one line. Maybe in another movie he was a mechanic, or the killer, or a love interest. Or maybe he played Jesus in some biblical film. But in this one he was just a seaman making a pass.

She thought of buying a bus ticket and moving away. Going to California. Hollywood, maybe. Get one of those expensive little dogs and be an actress. Buy a pair of glittery roller-skates and skate down Muscle Beach. She could act. She did so already. Pretending not to be disgusted by the writhing, sadistic and sweaty men that pummeled her night after night. But they were a means to an end. She went back to her apartment and counted the money she had stuffed in a coffee can. Fifteen grand and some change. It wasn't a bad start, she thought as she fed her mouse. He too was an extra in the movie. He symbolized something or other.

Maybe she would meet someone. Maybe someone on the bus, or maybe the bus driver. Someone at a stop along the way, maybe in New Mexico. Maybe an Indian. Maybe she'd live on a reservation. Have a brand new life and teach the kids about Jesus Christ because it was Easter, after all. So she gave up being a hooker and hung up on everyone who called and asked to see her. Then she bought the ticket to LA on a Greyhound Bus, which would leave Wednesday afternoon. She set her mouse free in the woods behind her apartment. He scurried away. She hoped he wouldn't get eaten, but she knew his uncertain fate was better than the certainty of the cage.

On Tuesday, the reverend left a message on her machine to meet. No words. Just a whistle. The chorus of "I'm in the Mood for Love," a song she remembered Julie London singing, the album of which her mom owned. She wanted to tell him in person that she was no longer doing dates because he had been her oldest client. The very first one, actually. She had seen him for three years and some months. So she met him at their usual time in the usual place. Tuesday at 3 at the motor lodge on Route 10 where the church kept a room, supposedly for battered women. And she told him, "I'm no longer doing dates, Bob. I'm quittin' hooking and moving to LA. I'm going to be an actress. Like Faye Dunaway."

Bob laughed. He put his hand over his mouth and apologized, but then laughed more. He said he didn't mean to laugh, but he didn't know what to say. Then he offered to pray for her and she smiled and accepted, closing her big eyes and bowing her head and holding her hands out for him to receive. He took her hands as though they belonged to him and stood there without saying a word.

"Are you okay, reverend?"

Bob didn't reply. He just stared down at that red carpet. Then he lunged at her and clamped his hands around her thin neck and squeezed. He held his breath for as longs as he could while he did, strangling her, grunting. Veins bulging in his face and neck. She collapsed on the bed and he fell on top of her. Her eyes bulging, frightened tears streaming down her cheeks.

"He's looking," she wheezed. "He sees you."

The reverend relented for a moment appearing frightened by what she said, but even more frightened by her smile as she was dying with her mascara smeared down her cheeks. God, how he loved her. He remembered how somebody once said we always kill those we love. How it never made since to him until now. Then he laughed maniacally and squeezed harder. The shower hissing in the background.

"And he shall forgive me," he whimpered.

She closed her eyes and there were stars and then there was darkness. And in the darkness she could see that velvet Jesus in her grandma's living room. She was a little girl again, just for a moment, innocent and perfect, looking up at Jesus, alone in that living room. All her life still in front of her. Any role she wanted to play, still hers to be had. There was a tear on Jesus' cheek. She could see it now, clearly, and as he faded from view the tear remained and she followed it until she died and the theater was empty.

The movie would go on without her. She'd never make it to Hollywood or ever have that small dog. The ticket in her purse would go unused. A seat on the bus would be empty. The fifteen grand would remain interred in the coffee can and later get pitched, presumably, being hidden in the grounds. She'd never roller-skate up Muscle Beach. The reverend would go on until he was caught for her murder, or maybe he would get away with it the way some people do. Who would suspect him after all? Him of all people.

The coroner knelt by her body that was tucked in the thick green body bag and looked up at a dumb-looking deputy in that motel room and grinned. "She's damn near the spitting image of that actress, ain't she?"

"What actress is that, Jim?"

"Well, just look at her, Tom. Faye Dunaway! She's the spittin' image. That Bonnie and Clyde was the worst damn movie I ever saw, but she made it worth watching. She sure did. What a goddamn shame."

"Hmm," the deputy replied. "I'm not much of a movie buff. She's pretty though. Was pretty, anyway."

"At least now she'll never get old. She'll never be lonely. Never be sad. And she is with the Lord. He didn't make something this pretty to give to the Devil." Then he zipped up the bag and they carried her away and Faye Dunaway took a role in a western and Daisy Good was forgotten as though she never was at all.

Comments

Post a Comment